Each player becomes an ingredient and plays kitchen tools. Performance of the score involves 2-4 players who each walk in a track on a 5x5 meter course. The tracks are broken into measured steps. Each of these steps is then broken into 4 beats. The score is written on the course and players strike their instrument as marked beneath their feet. Through movement and active listening players find a shared rhythm.

Tasty Score’s alternative notation and composition system spatially and musically examines the encounter between food and music. The first version was prototyped for the Art Prospect Festival 2018 in St. Petersburg. Tasty Score was inspired by the "Book for Tasty and Health Food", a Soviet cookbook dating back to 1939. This book serves as more than just a cookbook; it proudly boasts of a magnificent Soviet food industry that is both industrialized and efficient, and at the same time contains great abundance and variation - of both food and related culture. We were intrigued by the use of a cookbook as a means of representing and reinforcing a specific idea of Soviet life and wondered if we could invert this relationship. Tasty Score complicates our relationship to recipes and displaces the senses we usually use to interact with food. We hope this might open up new possibilities for thinking about our relationships both to international systems of agriculture and distribution and the plants, animals and minerals that end up on our plates.

We started the translation process with a simple prototype and playtest. The first prototype mimicked the staff notational system with wooden sticks on the floor and beats shaped like kitchen instruments. A classically trained violinist and a non-musician were tasked with interpreting the system.

Our second prototype set out to gain control of the translation from food to music through a more mathematical approach. First we created separate tracks for each player and a test composition revealed a need for a common musical approach. Because of the limited melodic possibilities of our kitchen instruments we chose rhythm as the commonality. We created a set length for each step and broke each step into 4 quarter beats.

The four track notational system as we initially imagined composing it

The four track notational system as we initially imagined composing it

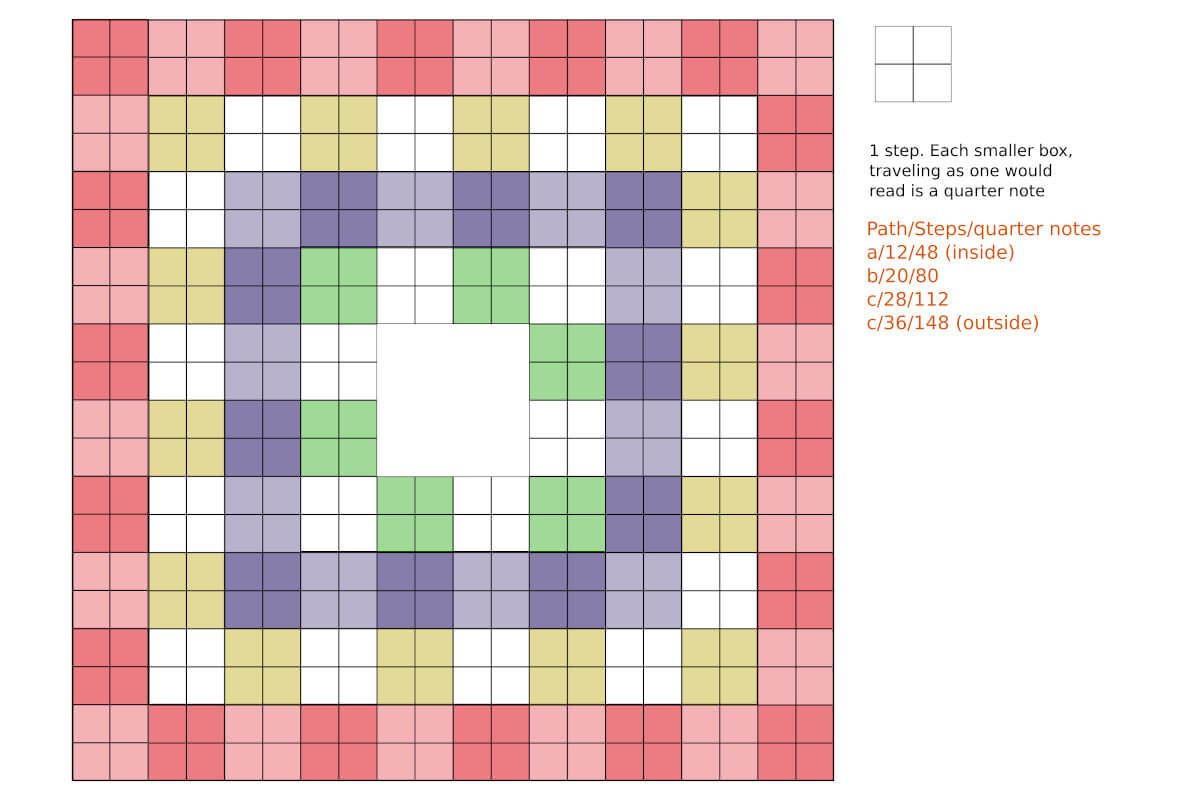

Once we created the nested tracks for players to walk in and assigned quarter beats to each step we realized that as players walked around the nested squares the structure of the rhythm would change as players continued to travel through their different length tracks. The inner track’s (A) 12 steps would resync with the outer track’s (D) 36 steps each time the outer player made a full rotation but the B and C track would resync sporadically with the other tracks until dozens of D rotations were completed.

A full rotation of the D (outer) track represented all the grams in the recipe. This meant the beats in the A (inner) track were repeated 3 times to complete the grams for the recipe. This somewhat counterintuitively meant that the proportionally largest ingredient often ended up in the shortest track. We then assigned multiple ingredients to the different lengths of the D (outer) track.

The PURR data patch for a version of Cod & Horseradish

The PURR data patch for a version of Cod & Horseradish

Since the different tracks did not stay synched in a simple way we had difficulty testing the scores quickly (each took about 30 minutes to play). We used PURR data to run through the scores in an accelerated manner as we experimented with different compositions.

Final selection of kitchen utensil/instruments

Final selection of kitchen utensil/instruments

Our initial compositions were made with kitchen utensils we had at hand. When we arrived in Saint Petersburg to prepare for the Arts Prospect Festival we spent our first few days at thrift stores and flea markets (particularly the spectacular Udel’naya Market, a great way to spend a Sunday) looking and listening to a variety of kitchen tools. Scores were then adjusted for these carefully selected instruments.

Once we had our kitchen tools and recipes translated into scores we had to decide how to present the scores to the players. We thought about picnic blankets, table cloths or other means of creating a highly portable score but the fall weather in Saint Petersburg threatened to make a soggy mess of any textile based solution. A stage assisted the players in finding a shared rhythm by amplifying the sound of their steps and also lent a subtle beat to each composition. The playfulness of a chalkboard stage made Tasty Score more inviting, allowed us to swiftly change out scores and left a trace of the players march.

Initial composition is done on a horizontal version of the score. To distribute the grams of each ingredient into the composition, generally the proportionally greatest ingredient is placed in A and divided by 3. Then B is divided by 2. Then C is divided by 1.3 and the remaining ingredients are divided into D1, D2, D3 and D4. This is based on a single full rotation of the D track representing the total grams of the ingredients.

Initial composition is done on a horizontal version of the score. To distribute the grams of each ingredient into the composition, generally the proportionally greatest ingredient is placed in A and divided by 3. Then B is divided by 2. Then C is divided by 1.3 and the remaining ingredients are divided into D1, D2, D3 and D4. This is based on a single full rotation of the D track representing the total grams of the ingredients.

The compositions were created with the aim of creating the widest possible diversity between the individual recipes within the strict methodology

- Cod and Horseradish includes a long break

- Brusselsprout Soup uses A, B and C tracks and has a call and response based expression

- Potato Pirozkhi with Mushrooms uses only track A and D

Track specific compositional considerations for Cod and Horseradish:

- A is condensed and complex

- B creates counterweight by being regular and repetitive.

- C is inconsistent and sparse (infrequent). It also follows a pattern and especially affects where A does not.

- D is structured and predictable.

- In the middle of the first round on all tracks, a longer break creates dynamics and anticipation.

Tasty Score: Saint Petersburg used weight as the sole compositional unit. We are currently developing versions that extend the complexity of the composition and translation system and might express: food production and distribution systems, changes to these and other systems across time, scarcity/abundance and other concepts.

“The Book for Tasty and Healthy Food” drew our attention to the cookbook as techno-cultural document with its obvious expressions of Soviet abundance. But every cookbook contains much more than recipes. There are assumptions about the ready availability of ingredients, manners in which those ingredients might already be processed, means and technologies available to the user of the recipes to further process these ingredients and much more. As Tasty Score grows we hope it might draw closer the connections between our bellies and the rest of the world written up so neatly in the cookbooks in your kitchen.